Oakville resident named Lewis County Tree Farmer of the Year

Wild Thyme Tree Farm will now be considered for state title

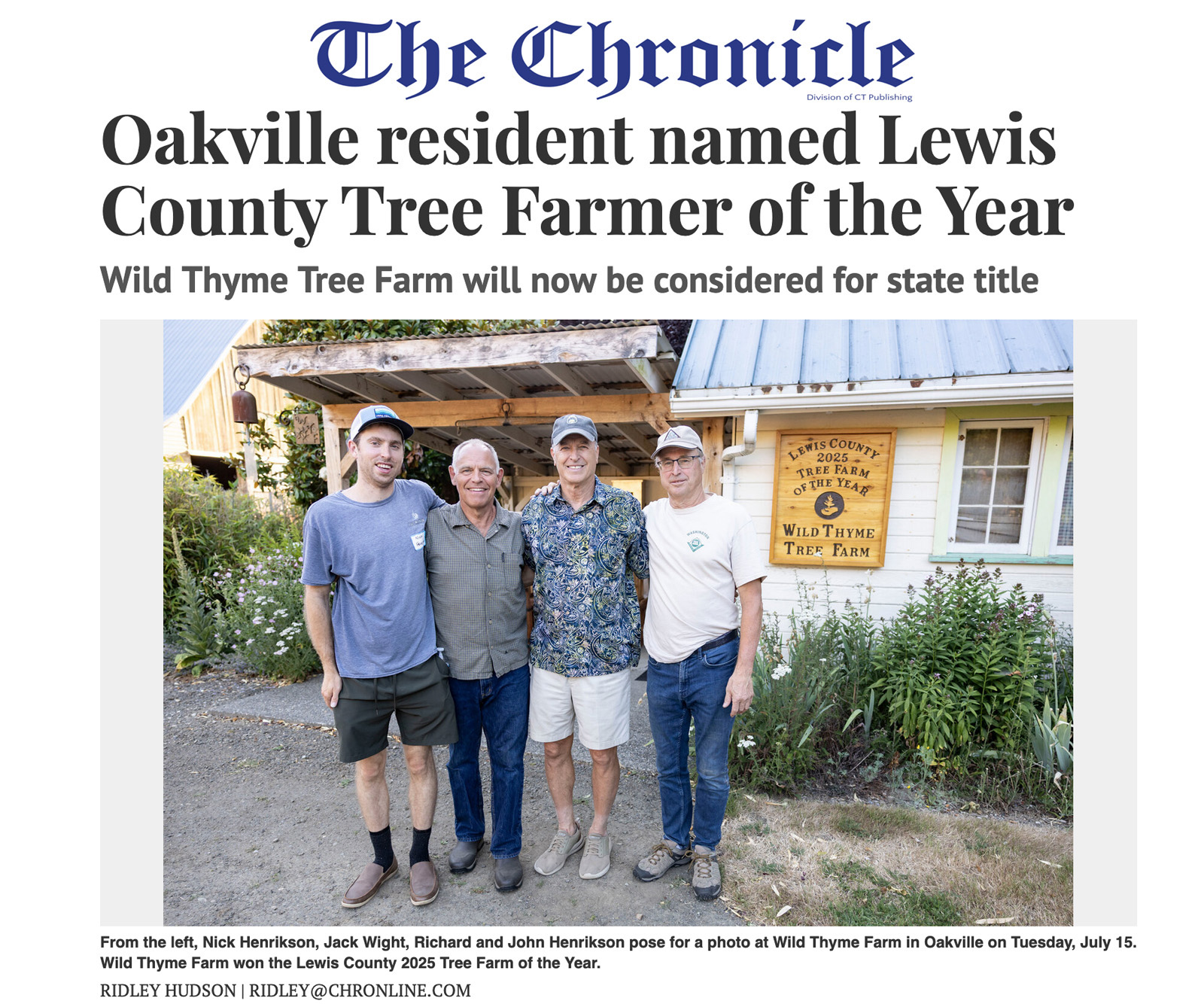

Photos by Ridley Hudson | ridley@chronline.com • Posted Friday, July 18, 2025 5:25 pm • Article by Jacob Moore / jacob@chronline.com

The Lewis County Tree Farm of the Year is a beautiful site to behold. It’s soaked in sun and covered in trees, it’s historical and it’s — in Grays Harbor County?

Washington tree farmer John Henrikson and the Lewis County chapter of the Washington Farm Forestry Association hosted a farm tour Tuesday evening to celebrate Henrikson’s selection as Lewis County Tree Farmer of the Year.

Even though Henrikson’s farm sits just on the other side of the county line in Grays Harbor County near Oakville, he is an active member of the Lewis County chapter and involved in three others.

As part of the celebration, Henrikson toured a group of association and local community members around the Wild Thyme Tree Farm, which he owns along with his three brothers, Richard, Robert and Jack.

Henrikson’s farm is very different from what many people might expect when they hear the words “tree farm.” It’s a far cry from your local Christmas tree U-cut operation or even the more traditional Douglas fir timber farm. The 150-acre tree farm that consists of rolling hills and nearby tributary streams plays host to four different kinds of forests and a couple fields for traditional agriculture.

During the tour, attendees mingled and chatted while Henrikson led a short hike around the property and shared his experiences. The majority of the land — approximately 100 acres — is dedicated to what Henrikson calls a native forest, which he manages to maintain a variety of tree species at different ages.

Henrikson also dedicates about 10 acres to wildlife habitat focused forest, mostly around fish-bearing streams, 5 acres to agro-forestry for nut and fruit trees that grow food and can eventually be used as timber, and another 5 acres to arboretum space where he has planted and managed rare trees such as coastal redwoods and giant sequoias.

During the tour, Henrikson asked his audience to follow him through nine different sites, starting in the property’s floodplain near its most significant wildlife habitat forest, followed by a walk through a small ravine and up the hill to show the full range of the forest he has created.

While following Henrikson, others, mostly fellow tree farmers, tried to keep up as he blazed a trail through the property that he so meticulously manages. It became clear speaking with attendees and overhearing conversations that Henrikson’s techniques on his farm are often unconventional.

Two tree farmers remarked that visiting the farm might give them ideas for a few experimental techniques to try on their own properties.

Others whose farms are focused more on timber production than agro-forestry and habitat noted that the farm was a very different type than their own, but nonetheless well managed. Bryon Loucks, an active member of the community and former Lewis County tree farm owner and tree farmer of the year winner, pointed out that the family had made a very unique and non-traditional tree farm profitable by taking some extra steps.

“This family is somewhat unique in what they’ve done,” Loucks said. “It’s what they want to do. They’re practicing pretty good forestry with what they’re doing. It’s not intensively raising a commercial product, but see, they’ve made that maple commercial with that saw mill.”

Unlike more traditional tree farms that often focus on timber harvests that come from thinning and eventually clearcutting plots of land, the Wild Thyme Tree farm is home to many trees that are not profitable as timber, such as maple. To turn a profit, Henrikson and his brothers mill many of the naturally fallen trees on the property into long wood slabs and go to steps to process them on their own before selling them to wood workers as material for countertops, tables or other wood products.

Tree Farmer of the Year

The award, which Henrikson received in February, is a bigger deal than some may realize, and apparently it may come with some added responsibilities. Along with hosting a tour and welcoming tree farmers from the surrounding counties, the award officially nominates Henrikson for consideration for the state Tree Farmer of the Year award. The winner of that award serves on the selection board the following year and often becomes a sort of unofficial ambassador for small forestland owners. The state title also nominates the farm for consideration for higher level awards regionally and nationally. Each stage involves tours, applications and more work and leadership.

Henrikson said he avoided the hot seat of Tree Farmer of the Year for a long time, but finally gave in this year when he and his family’s farm received the nomination from two different routes. Henrikson was nominated to be considered as state Tree Farmer of the Year both by an independent inspector as well as the Lewis County chapter of the Washington Farm Forestry Association.

“I actively resisted it for the better part of the decade,” Henrikson said. “I said, ‘no, no, no, I’m not ready’… It finally came from so many corners that I said, ‘fine, let’s do it’.”

While Henrikson sounds hesitant, it’s clear from his other involvement that his reservations come from perfectionism. After all, Henrikson already has many responsibilities in the community, serving in leadership roles both with the Washington Farm Forestry Association and the Washington Tree Farm Program.

In the past, he has also served on a number of state committees for different environmental and forestland issues, including the spotted owl, safe harbor agreement, carbon work groups and others.

He has been involved in the community for the better part of 30 years.

Wild Thyme Farm origins

Hearing about this very unique tree farm, one might expect that Henrikson and his brothers have been at this for years or even made careers of managing the farm.

That couldn’t be further from the truth.

Henrikson and his brothers first bought the land that is now called Wild Thyme Farm in the fall of 1986. The brothers, who originally hailed from the East Coast and were at the time scattered around the county, decided it would be nice to buy some land. The five young men were all single and without attachment at the time, and Henrikson, having spent some time in Washington in the off season from a job in Alaska, suggested the Northwest.

Once they decided to start looking, it didn’t take long for the brothers to settle on a place. Apparently, their current farm was one of the first pieces of the land the brothers looked at, and they snapped it right up. John will be the first to say that they were immediately in over their heads with the 200 acres of forest, farm and stream that also hosted a group of dilapidated buildings.

“That’s part of the process,” Henrikson said, “starting as a clueless landowner and becoming an advocate and even a mentor.”

Henrikson moved to the property almost immediately, and two brothers, Richard and Robert, who lived in California, would visit when they could. Unaware of what the land they had bought needed from them, Henrikson said the brothers didn’t address the landscape for the first eight to 10 years of ownership and instead focused on saving the buildings on the property, such as the old barn that’s still in use.

However, roughly 10 years after buying the property, a major ice storm in the winter of 1996 drove the brothers to learn more and become more involved in the environment around them.

“It wasn’t until the consequences of inaction drove us to take a more serious approach that we became active managers,” Hernikson said. “The cost of inaction was steep. It spoke to a huge missed opportunity and an unnecessary loss. Even though there’s elements of natural disasters you can’t stop like tornados … With things like ice storms and wildfires, the way you mitigate the damage can change the outcome.”

Henrikson has now become an involved manager of the forestland on the family property, especially since retiring from his first career in the software development industry in recent years.

As he traversed the land for the tour and many looked on in awe at the work he was doing, he spoke frequently of the next steps, the little tweaks and the progress he hopes to continue in the future.

While he said he never imagined this is what the farm would become when he and his brothers first bought it, he said it’s simply where he has found himself while listening to the environment and the community around him.

“You start out with a plan and how you’re gonna manage the land, and if you really get into it, you get to the point where the land starts to tell you what to do,” Henrikson said. “You start to get feedback from the land … You start to get aligned with that, and you really get good results.”